By Mikaleen Bohanick and Cynthia Rice

Our wire study may have officially started during a January teacher professional development session. But the origin for the idea began a few months before that when one of the children in our Head Start classroom was constructing a tower.

Late in the fall, four and five-year-old children at the Carmichael Head Start Center had been very interested in using recycled materials to build structures. One of the children shared that her mother had traveled to New York City. She decided she wanted to create skyscrapers and towers using Styrofoam.

But the structures did not stand up well. We asked her what she thought she could use to help support the Styrofoam, and she said she needed some wire. She chose a thicker wire because it was “hard.” She cut the wire and placed it between the long pieces. This worked!

Wire had been available to the children in our classroom, and a few would make necklaces and bracelets. But she was the first one to use it in this different way.

The option to formally begin a wire study in the classroom was presented that January by Dr. Karen Haigh and Kristin Brizzolara, consultants providing professional development at Child-Parent Centers. A study is an investigative and explorative process led by children which includes their theories about how they view the world, what they think about and how they understand it.

Teachers provide meaningful provocations for the children to help them explore their environment more deeply. These provocations often turn into short- or long-term studies, when children continue to investigate over days, weeks and even months.

Teachers support the children by listening and documenting where children want to take their theories next.

We decided to re-introduce wire to the children after the January session because we wanted to see where a wire study would take us: how we would plan, what we would provide for the children, what the children’s thinking would be, how to provide varying entry points to the study, and how to support different learning abilities.

So, during our large group meeting, we discussed materials that were being used. The child who had created the towers talked about the wire that she had used.

Several of the children discussed how the wire was used to support the towers. We introduced different kinds of wire and asked the children what they knew about wire and it was made available to them to be used how they wanted.

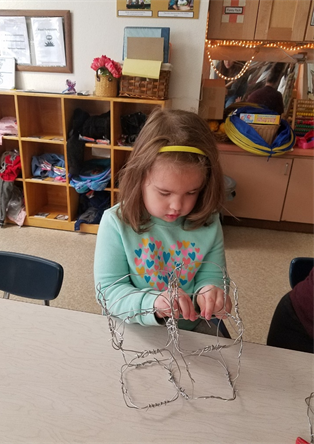

They began by using chenille sticks/pipe cleaners. They created squares by tying the wire around a square wooden block. Then they weaved more of this wire in between the squares and decided to connect each other’s pieces together.

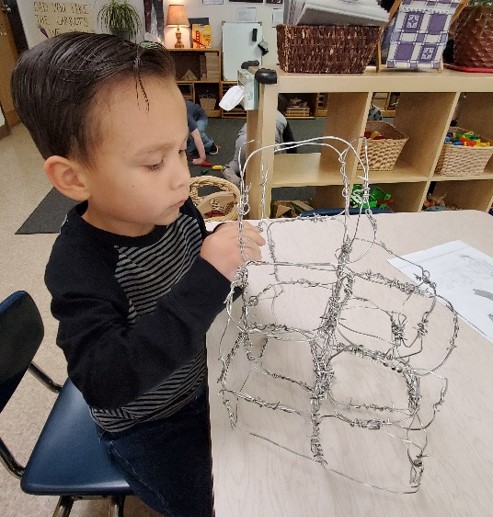

After working with this for about a week, they decided to try making squares with a different wire, an aluminum wire. First, they manipulated the wire to understand its properties. Then they began working with it. They thought that this wire would be more stable and say in the square form.

One child worked on this structure every day for a week. He waited for other children to make and connect the squares of wire and then began to stack and connect them into cubes. He then took the cubes and connected them. He would cut a piece of wire and wrap it around the pieces that touched. Before he connected the pieces, he would look at the structure and the cube to decide where it would fit best.

We provided new tools, wire cutters and different kinds of pliers, to use with the wire. We offered books about wires, such as The Mighty, Mighty Construction Site and Tool Book along with other items — beads, pipe cleaners and different types of recycled materials — to continue to determine their interest.

Children are very capable. They can use wire cutters and pliers. We talked about safety, how and why to use the tools, how to hold them. The tools were used while one of the teachers was present to provide support.

The children tried to cut this thicker wire with different cutting tools. They had a hard time and were not able to cut it. But then they found out that if they pushed down on the wire, it would bounce back.

As we observed this emergent learning, it helped us to plan based on the skills and abilities of the children, making sure we provide provocations to continue to hold the children’s interests and support their growing capabilities.

Some of the children added beads to the smaller pieces of wire and added those to the thicker one. Then a child wanted to wrap chenille stems around it. Other children joined in. They wanted to hang up the structure, possibly outside.

The children continued to develop an interest in creating with the wire. Every day there were children working with wire in one capacity or another. Their creations became more and more intricate as they began to understand the properties of the wire.

During the wire study, some children worked on the wind chime while other children were working on other wire projects. Several wire activities were happening at the same time.

With the wire study, we learned to be patient. We were glad the seed was planted, and it was worth it. Just as the children are emergent learners, we, as teachers, learn alongside them, seeing what works and what does not and finding new ways to promote learning opportunities.

Our study went on for about 6 weeks. We could see the emergent learning each day. We would have liked to include the other classes in joining our discovery.

After manipulating the wire and working with it, we wondered if we could have worked with the children and helped them see how wire conducts electricity through a science experiment: Connecting wire to a battery to light up a bulb, as an example. We were also thinking about other types of wire, such as chicken wire, to see how the children would use it. We would have liked to add clay. We were planning on seeing how the children would use wires along with the clay. We were offering books of sculptures in the classroom to spark interest.

Children have the right to learn at their own pace, with their own interests and engage in exploration. They need to be able to use all their senses to understand the world around them. We, as teachers, follow the children’s interest, we need time to think about what we observed and think where it will take us and the children, think about how we can help children learn new skills and abilities.

We have been working on studies for several years. With each study, we learn new ways to provide provocations, think more deeply about how the children are learning, observing as they develop new skills and providing for the emergent learning.

By working together, and collaborating with other staff, we are able to get new ideas to provide deeper learning opportunities for the children.

About the authors

Mikaleen Bohanick is a Head Start Teacher and has worked with Child Parent Centers, Inc. for 25 years. She worked at the Pueblo del Sol Head Start for 11 years and has been at Carmichael Head Start for 14 years. She has a BAS in Early Childhood Education. She also worked with the CDA council as a PD Specialist conducting CDA reviews. Her favorite thing about being a teacher is seeing the moment a child understands something new and that they realize can do it.

Cynthia Rice is a Head Start Teacher and has worked with Child Parent Centers, Inc. for seven years. She also has worked in two other preschools prior to working in Head Start. She earned a CDA and is working towards a degree in early childhood development. By working with other teachers throughout her career, she has learned many skills and valuable ways of teaching. Her favorite thing about teaching is the satisfaction of seeing a child succeed in accomplishing something that was very hard for them to do.

About Child-Parent Centers, Inc.

Carmichael Head Start Center in Sierra Vista, Arizona is one of 40 centers funded by Child-Parent Centers, Inc. the grantee for Head Start and Early Head Start in southeastern Arizona. These programs serve approximately 2900 children (birth to five years) and their families within a five-county area of Cochise, Graham, Greenlee, Pima and Santa Cruz.

Ongoing professional development for teaching staff is an agency commitment that is planned and scheduled within each calendar school year. The January in-service usually focuses on a principles related to our Reggio inspired curriculum approach.

Our curriculum, The Languages of Learning, is locally designed and meets State and Office of Head Start standards. The guiding tenets are: The Image and Rights of the Child, The Image and Rights of the Parents, The Image and Rights of the Teacher, Observing and Listening, Role of Environment as a Teacher, Documenting, Creativity, and Imagination. For the sake of this story, there is an emphasis on the role of on-going professional development and the role of materials (the hundred languages) that demonstrate the many ways children express their thinking, and understanding about their life encounters.

All photos courtesy of Carmichael Head Start Center and Child-Parent Centers, Inc.